This zine is the fourth & final in the menu series. It is the collective work of over 60 artists, authors, activists and aliens. All contributions were made and submitted separately. Below is a selection of the entries from the zine. Please check out the artists and support $$ their work!

We were able to print 4,000 copies of menu 004 --- twice as many as last year --- due to the support of friends and the generous $$ contributions from 56+ benefactors.

THANK YOU to everyone who opened their homes, shared their club nights, played at our fundraising events, threw cash in a turquoise pumpkin, or otherwise pitched in to reach our fundraising goal.

While this is the final zine in this series, we believe in the power of printed media so please keep your eyes open for future printed matter.

If you have the means please consider a donation to help us cover SHIPPING - venmo - @elleb33

Get in touch - hey@rave.cafe

zine selections

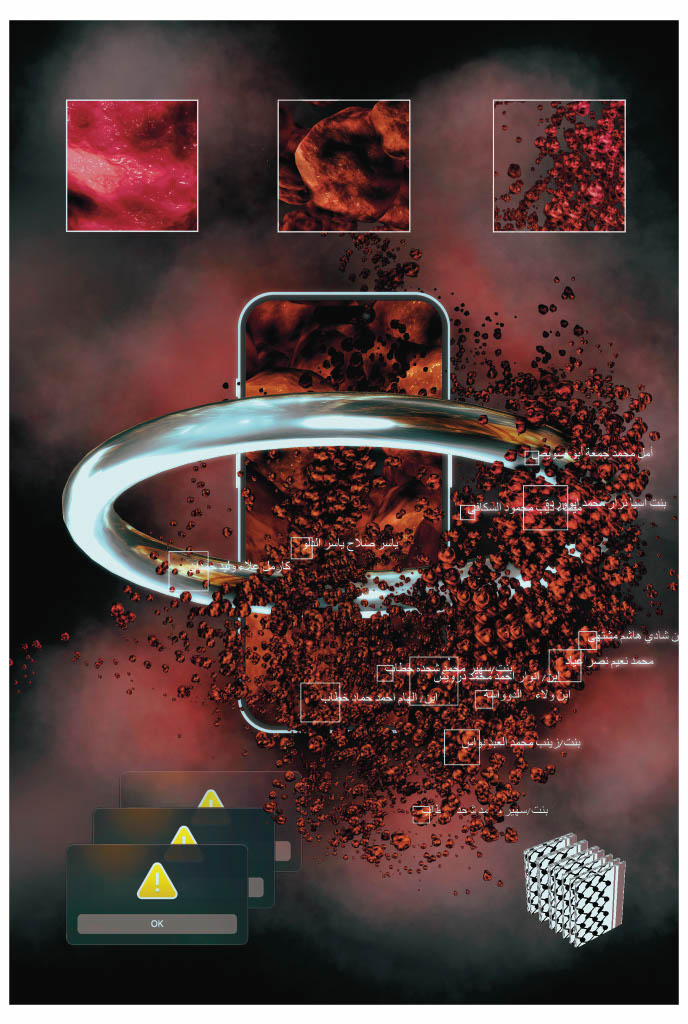

Janus Rose – Remote Viewing #1

Inspired by the paranormal practice of "remote viewing," in which practitioners claim the ability to mentally perceive distant subjects and places, Brooklyn-based artist Janus Rose meditates on our technology-mediated observation of state violence and genocide. Utilizing procedurally generated graphics, this first piece in the series dynamically tracks objects through a series of virtual cameras, assigning objects names pulled in real-time from a public dataset[1] of Palestinians killed by occupation forces in Gaza.

[1] data.techforpalestine.org/docs/killed-in-gaza

Janus Rose is a digital artist, journalist, and electronic musician hailing from New York City. Her work has been featured in digital and print publications including e-flux Journal, Dazed Magazine, VICE, and Al Jazeera. She is the founder of SOFT_RESET, a local party featuring dj's and live hardware artists that aims to explore new horizons in experimental club and bass music.

Niyah West - Brickline & Rose (Deterred)

It always gave me hope

Chipped gravel eroded from its place in the sidewalk

What emerged gave off hues of purple, yellows, stem and bud.

You know, the good stuff

Petals of hope

genus sprouting through small opportunity

It always gave me hope

Sandstone & bay windows

A front entrance porch

Transformed into a wild green display

At the door is Ms. Mary

Fifty years of nurturing

This Brickline & Rose

This street of hope

Somewhere in a quiet corner of the city

Is a neighborhood untouched

By the bustle of economy

Ms. Mary wakes up early

Watering the cracks in the sidewalk

Everything must grow

Oh these petals of hope!

Please let them grow

There are many Ms. Mary’s

On Brickline & Rose

Aaron Vansintjan - Social media is dying. How I am learning to live without it

This is what Naomi Klein calls a Doppelganger, a second self. The more we post, reply, like, and share, the more we put ourselves in the shoes of our Doppelganger: what do people think about our posts, replies, likes, shares, and the identity that we’ve created? Our Doppelganger starts to split us in two: one who maintains their life, eating, working, sleeping, and another who lives a filtered version of the life we’d like to lead and like others to believe we lead.

As a published writer, I have felt the negative impact of this double life. I post about some interview I did, or a positive review of my book, and get likes and applause. Meanwhile, in my day to day life, I’m obsessively looking at my dwindling bank account and applying to welfare and can’t sleep at night from anxiety about how I will pay rent. I’m creating a Potemkin village of my own brand, a façade—telling the world everything’s great, faking it until I make it. I am like Demi Moore’s character, Elizabeth Sparkle, in the movie The Substance, living less and less in my own body and more and more in the body of a young, successful, sexy brand. The irony is, the more energy I spend maintaining this brand of a successful writer, the less time I have to write.

What’s worse, that creative act of writing, taking a photo, making art, then gets funnelled into the attention economy. If I make something that gets traction, other people pay attention. But after the initial dopamine rush, I don’t see the benefits personally, except feeling pressure to make yet more content, to keep riding that high. The attention economy extracts my creativity and, by constantly demanding more content to appease the attention economy, effectively exhausts it. Social media is designed like a treadmill, always accelerating, and if you stop, you drop out.

Now, we’ve reached an even more pernicious stage of social media’s development: enshittification. It’s all shit. On Facebook, I scroll the news feed and all I see is pages that show me random memes, tailored to my tastes, with thousands of likes. I can’t turn these off, I have no choice but to see them. On Instagram, most of what I see is just content stolen from elsewhere, reposted and edited to please the algorithm. When I watch this content—whether it’s AI generated or by people—I think, how can I even compete? I will never have the time or resources to create and post endless content—my creativity just doesn’t work that way, isn’t fast enough. And posting in this frenetic way would feel false, wrong, unlike myself.

There was one kind of activity that, for some time, did feel useful to do on social media: politics. We could express dissent, and solidarity with others. We could organize and show up to protests in numbers not before thought possible. But here too, there was trouble. During Black Lives Matters protests, the influencers began to show up, with their selfie sticks and competition for attention. In the words of philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Social media makes want to be a Thing, creating an identity about our politics, beliefs and ideas. We began to think of ourselves like corporations and politicians: compelled to make a statement about every atrocity, then finding fault with others’ statements. It was exhausting. When Israel began its genocide against Palestinians, and so many arose in protest, we turned to the platforms again. We hoped that we could at least, at the very least, use this broken medium for protesting the genocide going on. But after an initial wave of hope, even that possibility is being destroyed.

Just a few days ago, the United States Department of Homeland Security announced a new policy: that it would look at the social media of every applicant, and refuse visa applicants on the basis of “antisemitic content.” We all know what this means: anyone who ever posted about Palestine will be screened and denied entry. And we know this is not where it ends: eventually, any critique of capitalism, transphobia, racism, white supremacy, or patriarchy will make us a target of the state. We will begin to limit ourselves from posting—for fear of personal repercussions, yes, but also for fear of implicating those we care about. If we are all hiding our true beliefs on social media, then what will remain? Our carefully sculpted brand.

How did it get to be this way? I think part of the answer is in the way, in its very design, social media understands social relationships. In the book Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, Samuel Delaney juxtaposes “networking” with “contact encounters”. Networking is the kind of socializing that happens at conferences, where people wine and dine, hoping to be noticed and make it big. Here, there is little cross-class interaction, and what there is becomes largely competitive, with people of lower hierarchy competing against each other for the attention of those at the upper echelons.

In contrast, “contact encounters” happen randomly, in public spaces like at the grocery store, or at the movies, or the dance floor. Often, but unpredictably, these encounters lead people to make connections that are long- lasting and mutually beneficial. For example, at the pornographic movie theaters that Delaney frequented in Times Square, men met other men, across class divides, brought together by their sexuality and desire, but forming lifelong connections. These spontaneous interactions saved many men from overdoses, destitution, homelessness, and loneliness.

The story of how this essay came to be is a perfect example of why raves are such great places for contact encounters. Two years ago, I was in Detroit at a rave. I did not realize I was severely dehydrated and experiencing a sugar crash. L + D approached me and offered me snacks, electrolyte packs, and a copy of the Rave Cafe zine. After a short conversation about the zine and lots of sugar and water, I was revitalized. A few months later, I remembered the moment with gratitude and sent them my book about degrowth. Two years later, I am writing an essay for their new issue, whose theme is degrowth. That’s a contact encounter.

Compare this to the kind of posturing and self-promotion that has become so ubiquitous on Instagram, where hopeful DJs, writers, influencers, and artists post tailored content to promote their brand. We start with the hope of connecting and finding like-minded creatives, but we end up spending more time counting likes and followers. It’s like being a guppy in a fishtank wanting nothing more than to be noticed by the sharks.

I’m old enough to remember the first moment I logged on to Facebook, the first “social network”, where, we were told, we could meet and connect with the world. We hoped that chance encounters would lead to new, convivial relationships based on shared passions. But because of its very design, it became more about self-promotion, and turned into a place of competition, surveillance and exploitation. We need spaces that foster non-competitive cross-class encounters. We need to venture out of cyber waters to shake hands.

This is what the rave has become for this generation. In dance, we lose ourselves and find ourselves. We disassociate and reassociate, losing and regaining attention freely. We randomly meet others, we break through class and race and gender, fluidly experimenting with new boundaries. We meet people from entirely different backgrounds, in a mostly non-competitive way.

The rave is one way out. There are other strategies I’ve experimented with, as I learn to live without social media. Here are 11 of them:

- Enshittification means you can no longer compete. You don’t have to.

- Use social media. Do what you have to to stay alive. But use it to build an exit: get each follower to sign up to a mailing list, or move to a Discord channel.

- Don’t be a Thing, do a Thing. Join an organization. Be uncomfortable, multiply concrete encounters.

- Learn to tell apart the Thingers from the Doers. There are Thingers who claim to be Doers, but whose goal is to be a Thing and expand their reach. They will take it all, if you let them.

- Use AI. Don’t be afraid of it. If it makes your job easier, go for it. If you can use it to hijack the discourse, why not? But, use it to speed up your exit.

- In an authoritarian surveillance state, you can no longer just post what you really mean. You don’t have to. Say what you mean in meetings, face-to-face interactions, in poster campaigns, leaflets, stickers, and anonymous signal groups.

- Counter-branding. If we must go on social media and play the game of self-branding, take the self out of it. Create fake brands, a kind of online graffiti, subverting influencers. Speak like the status quo, but don’t mean it, making the status quo sound absurd. Hijack the imagery of capitalism and use it against itself. Know that counter-branding will take a lot of energy to maintain. Plan for the exit.

- Tunneling. There are small online communities under the rubble of social media. Tunnel between them and connect them. Always assume they are surveilled, abandon them when they collapse. Keep moving. Tunnel onwards.

- Whatever you do online, do it efficiently. Whatever gets you to the dance floor, the drawing board, the sex party, the garden, the library, the protest, the tenant union, the bike ride, the book talk. Download app. Post content. Delete app.

- AI art is for fascists, obsessed with purity and perfection. Make ugly shit. Be a degenerate. Use your emotions and get them out. Be primitive, listen to your darkest desires, write about them, make art about them. Don’t worry about finding your technique, there are no rules. Make bad art and make it often. Make it for your friends. Make it for the outcasts. Make it to share with one or two people you’ve never met.

- Print it. Hold it in your hands. Give it away.

Thanks to Celia for her edits <3

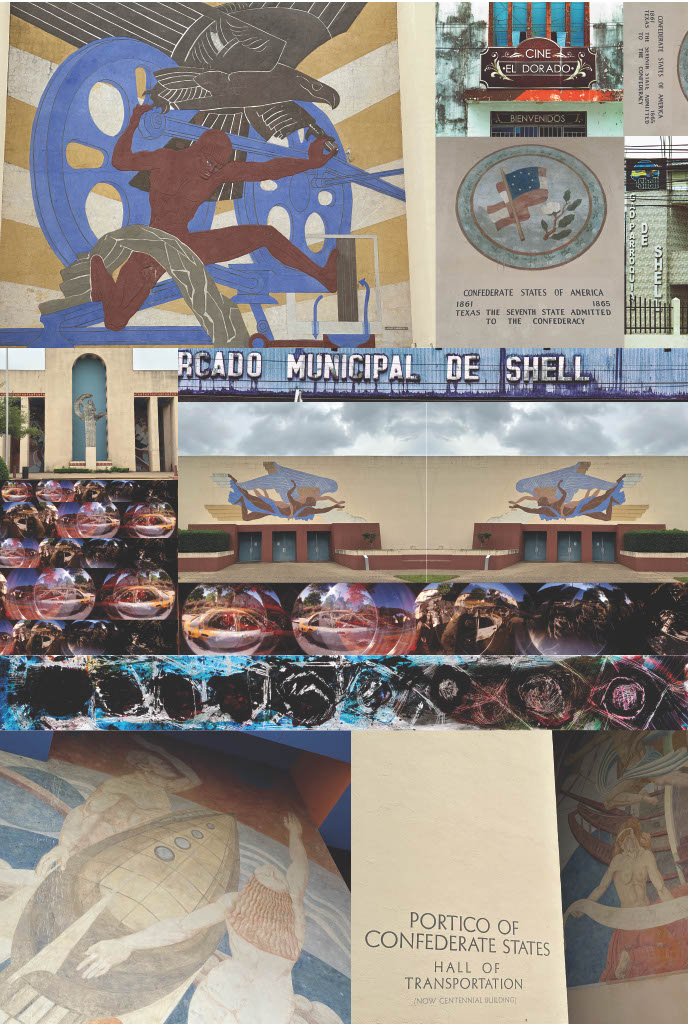

M. Woods - The Anatomy of a Con State with Car Bombs

upcoming

EVENT DETAILS:

Clown Show Prison X Green Point Film Festival present BODY PROP

W/ director M Woods in person

259 Green Street, Brooklyn

MAY 30 | 7PM

M. Woods (He/Him/They/Them) is a multidisciplinary artist implementing avant-garde strategies under the studio name “Disassociative Productions”. M is a first-generation US citizen, born to a Costa-Rican/Ecuadorian mother. M uses immersive time-based spectacle and constructed trances to navigate the internalized socio-political topographies of addiction, mental and physical disability, malignant nihilism, and white supremacy. M’s work deconstructs the post-911 acceleration of hyperrealism and (media)drug dependency, documenting the spread of solipsism in a media environment dominated by corporate neo-fascism.